From GuruFocus.com

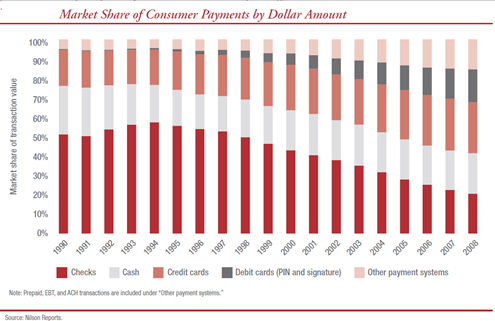

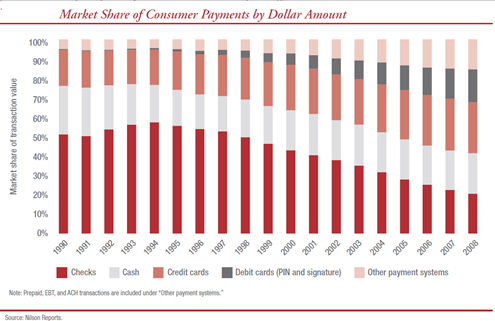

MasterCard is in the business of processing payments and licensing its brand. It does not issue cards or extend credit. Basically it collects royalty on worldwide consumption. The economics of the business are very attractive. It’s in a duopoly position in most markets with its only competitor, Visa. MasterCard’s revenue has grown by 1.6x from $3.3 billion to $5.4 billion in the last 5 years since its IPO in 2006. Revenue is expected to continue to grow at low-to-mid-teen rates as electronic payments take its share from traditional forms such as cash and checks globally. Furthermore, the business requires very limited capital and almost all of it is fixed in nature – in its data centers and for marketing & advertising. These expenditures are growing at a much slower rate than revenues, hence there’s massive operating leverage. Operating margins have expanded from 20% in 2006 to 50% today. EPS has grown faster than revenues and by 3.7x from $3.52 in 2006 to $13.08 today. Amazingly, Mr. Market is offering this “wide moat” business at two-thirds its conservatively assessed intrinsic value because of valid but potentially overblown concerns over the impact of a recently passed regulation called Durbin Amendment.

Business Model:

MasterCard operates a ‘Four-Party Payment System’ that processes information and routes transactions between the cardholders’ and merchants’ financial institutions in fractions of a second. It is so called because the network links together the four parties involved in each transaction:

The cardholder’s issuing bank, also known as the issuer, that markets and issues payment cards to the cardholder.

The cardholder who can use his payment card almost everywhere in place of traditional forms of payment such as cash or check.

The merchant who accepts the payment card in exchange for goods or services and receives guaranteed payment.

The acquirer that contracts with the merchants and provides them with payment card acceptance and processing services.

Flow of transaction information begins with the purchase, when the cardholder provides the payment card information to the merchant. The merchant sends the card information to the acquirer, such as First Data, through its point-of-sale terminal, which in-turn passes the information along to the issuer, such as Bank of America. Card networks, such as MasterCard, typically provide the link between acquirers and issuers over which this information flows. The network routes information first to authorize and then to settle the payment. To settle, the issuer obtains funds from the cardholder - $100 in this example – which it can pay the acquirer. However, the issuer retains a portion of the funds an an “interchange” fee. In this example, the fee is $1.50 and the issuer send $98.50 to the acquirer. The acquirer charges the merchant a processing fee, “merchant discount fee”, of $0.50 and deposits $98 in the merchant’s account. The merchant service charge is the total cost of processing the payment and in this example is $2. The card networks do not get compensated from the interchange fee or the merchant discount fee. They usually charge the issuer and the acquirer various network usage fees based on many factors that are not clearly disclosed, but whose key drivers are the gross dollar volume and the number of transactions flowing through their network. In general, the network fees amount to tiny fractions of the interchange fees and the merchant discount fees.

Like MasterCard, Visa also uses a ‘Four-Party Payment System’. Transactions on the other two major card networks – American Express and Discover – generally involve only three parties: the cardholder, the merchant, and one company that acts as both the issuing and the acquiring entity. Merchants that choose to accept these two types of cards typically negotiate directly with American Express and Discover over the merchant discount fees that will be assessed on their transactions.

In a ‘Four-Party Payment System’, the interchange fees generally account for the largest cost of acceptance of the payment cards. Even though these fees are earned by the issuer, they are set by the card networks. This may sound surprising to those who are not familiar to the payment card market, but economists have noted that the payment card market is an example of a “two-sided” market. In such a market two different groups – merchants and consumers – pay different prices for goods offered by a producer.

Other two-sided markets include newspapers, which charges different prices to consumers who purchase the publications and advertisers that purchase space in the publications. Typically, newspapers offer low subscription rate or per copy price to attract readers, while funding most of their costs from revenue received from advertisers. Charging low prices to encourage large numbers of consumers to purchase the newspaper increases the paper’s attractiveness to advertisers as a place to reach large number of consumers, and thus allow publishers to charge such advertisers more.

Similarly, the card networks use interchange fee as a way to balance demand from both consumers (who want to use cards to pay for goods) and merchants (who accept cards as payment for goods). As with newspapers, the cost to both sides is not borne equally. To attract a sufficient number of customers to use their cards, card networks compete to attract financial institutions to issue them (by compensating them through the interchange fee). Just as readers have a variety of sources from which they can receive their news, consumers also have a number of different methods (such as cash, checks, or cards offered by various issuers) by which they can pay for goods and services. The financial institutions compete to attract consumers to use the card issued by them by charging them a low fee or often offering them a negative cost through rewards. This price structure is critical to encourage the consumers to carry the network’s cards in place of cash and checks. Once the circulation of cards for a particular network goes up, network effects kick-in, leaving merchants with limited choice but to accept the network’s payment cards. Like the case of advertisers in the newspaper market, the revenue for funding the costs of this system is mostly provided by the merchants. Unlike the advertiser’s case, the benefits that the merchants receive for participating in this system may not be obvious to you. Here is a list:

Less vulnerable to theft and can provide safer workplace to employees.

Faster and guaranteed payment for transactions (unlike checks).

Faster checkout.

Benefit of increased sales as more people are attracted to stores that accept their card.

Is more cost-effective than merchants issuing their own cards or some other form of credit.

Easy record keeping

As merchants acceptance for a network’s card goes up, issuers’ preference for the network also goes up. This is evident from the fact that Visa and MasterCard have dominated the credit card purchase volume for years, and it has been very difficult for Discover to gain a higher market share. The above attributes of the business model makes both, Visa and MasterCard, a “wide moat” business.

Business Overview:

The card-based forms of payments licensed by MasterCard fall in the following categories:

"Pay Later” Cards that allow the cardholder to access a credit account (Credit)

“Pay Now” Cards that allow the cardholder to access a demand deposit or current account (Debit)

Signature based debit card – primary means of validation is signature at point-of-sale

PIN based based debit card – primary means of validation is a PIN at point-of-sale

Cash access ATM card – access cash at ATMs by entering a PIN

“Pay Before” Cards that allow the cardholder to access a pool of value previously funded (Prepaid).

In general, credit cards carry the highest interchange fees, PIN debit the lowest, and signature debit and prepaid cards in between. As a corollary, credit cards usually carry the highest rewards for the consumers and the PIN debit cards the lowest.

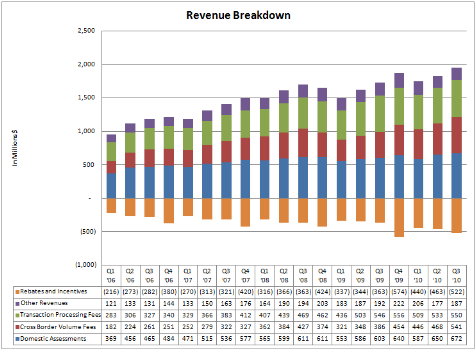

MasterCard generates revenues by charging its customers (issuers and acquirers) fees for providing transaction processing and other payment-related activities and assessing its customers based on the dollar volume of activity on the cards that carry their brands. Their net revenue is categorized in five categories:

Domestic assessments: Based primarily on the volume of activity on the cards where the merchant country and the cardholder country are the same.

Cross-Border volume fees: Based primarily on the volume of activity on the cards where the merchant country and the cardholder country are different.

Transaction processing fees: Charged for both domestic and cross-border transactions and are primarily based on the number of transactions.

Other revenues: Examples of other revenues are fees associated with fraud products and services, consulting and research fees etc.

Rebates and incentives: Varies based on type of rebate and incentive – hurdles for volumes, transactions or issuance of new cards etc.

MasterCard’s pricing is very complex and is undisclosed, but it depends on the following factors:

Domestic or Cross-Border.

Signature-based or PIN-based. Signature-based generates higher revenue.

Tiered-pricing with rates decreasing as customers meet incremental volume/transaction hurdles.

Geographic region or country.

Retail purchase or cash withdrawal.

Financials:

Net Revenue has compounded at an average quarterly rate of 4.5% in the last 15 quarters since Q1 ‘06. Note that revenue from international transactions (Cross-border volume fees) is becoming a bigger percentage of the overall revenue as seen in the revenue breakdown chart below.

Revenue growth can be attributed to two key drivers (i) gross dollar volume flowing through the network and (ii) number of transactions processed. GDV attributed to credit in the US is slowing whereas debit in US as well as rest of the world (ROW) has been growing rapidly. Also, GDV flowing from rest of the world is a much higher percentage today than in 2006. GDV grew quarterly at an average compounded rate of 3.2% and transactions at an average compounded rate of 3.4%. The faster revenue growth can be attributed to higher cross-border volume transactions and/or pricing changes.

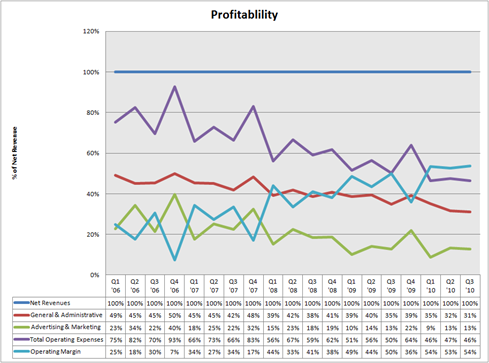

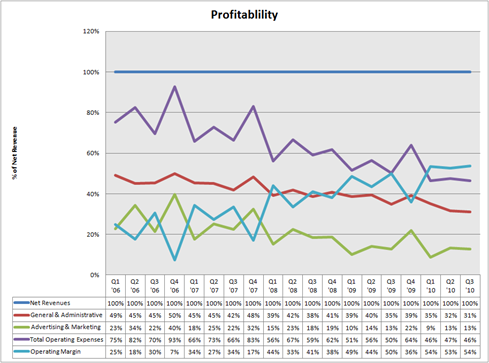

MasterCard is among the most profitable businesses in the world. Because of the predominantly fixed cost nature of its business, it has massive operating leverage that is evident in the chart below. Operating expenses have come down from 75% of net revenue to 46%. In the long-run, MasterCard should be able to maintain operating margin in the range of 40-50%.

These numbers are based on adjustments made to income statement. To make these adjustments, we ignore one-time events (gains as well as losses) and litigation costs. Even though we ignore litigation costs, it is expected to be an on-going cost and cannot be ignored in our future outlook or valuation of the business. It helps to do so here only to highlight the operating nature of the business.

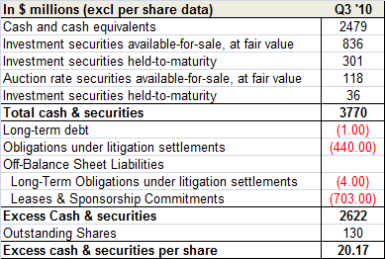

MasterCard has a pristine balance sheet with no debt and $3.7 billion of cash and securities ($29 per share). It has reserves for pending obligation settlements and for off-balance commitments for leases and sponsorships. Adjusting for these ‘debt-like’ liabilities, it has excess cash & securities of $20 per share.

Valuation:

Mr. Market has offered this wealth compounding machine at low valuations as today only a few times before in its trading history – (i) during the great recession in 2008 and (ii) in Q2-Q3 ‘10 when a law to regulate the interchange fees and the payment card business was passed (also known as the Durbin Amendment – more on this later).

P/E ratio of 17.20x in the chart above in the 'today' column does not take into account the excess cash on MasterCard’s balance sheet. Taking out the $20 excess cash from the price for MasterCard share of $225 today gives a lower P/E ratio of 15.6x. For a business with growth prospects and profitability like MasterCard’s, it ought to trade at least at a P/E ratio of 18-20x + excess cash on balance sheet. We believe this will require patience though. Once the regulatory clouds clear and MasterCard can prove that it can manage through Mr. Market's current concerns, Mr. Market will award MasterCard’s shareholders by expanding its P/E ratio to this range (or even higher depending on its mood). This is very similar to Mr. Market’s response from Q4 ‘08 at the peak of the recession through Q1 ‘10. The matrix below shows the skewed risk-reward profile for investing in MasterCard today. We agree that it was cheaper in Q2 ‘10 when it hit a low of $191, but I believe that today's price offer a good enough margin-of-safety. Timing the market is not a value investor’s forte. We would rather take Mr. Market’s offer today to build a position and be ready to average down our purchase price in case of further volatility.

Durbin Amendment:

Why is Mr. Market unenthusiastic about MasterCard today? The reason - a particular amendment, “Durbin Amendment”, to the Dodd-Frank Act Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act that was passed by the Congress in the summer of 2010. For those not familiar with the Dodd-Frank Act, its main provisions are aimed squarely at large banks and other systemically important financial institutions in response to the recent financial crisis. The Durbin Amendment has provisions that aim to regulate the credit and debit business in the US. Interchange fees and related payment card network rules have been the subject of intense regulatory scrutiny and litigation globally for the past decade. The Durbin Amendment marks the first time these fees will be regulated in the US.

This section of the article is broken into the following sub-sections: (I) Why regulation (ii) What is Durbin Amendment (iii) Fed’s proposal (iv) Possible Impact of the Proposal.

(i) Why regulate the interchange fees?

Why regulate the interchange fees? US interchange fees are the highest in the world. The total amount of interchange revenue from credit and debit transactions is unknown but it is estimated to be about $48 billion. As per one estimate we have read, roughly $31 billion is from credit interchange and $17 billion from debit interchange. The chart below shows the breakdown further:

As per the GAO report on the interchange fees, one of the reasons for the rise in the interchange fees is increased competition among card networks for financial institutions to issue their cards. Although increased competition generally produces lower costs for goods and services, such is not the case for this market. Before 2001, Visa and MasterCard had exclusionary rules prohibiting their members institutions (they were an association then, not a private or a publicly-owned enterprise and their members were also the issuers) from issuing cards of the competing networks. In 1998, DOJ initiated a lawsuit charging, among other things, that Visa and MasterCard had conspired to restrain trade by enacting and enforcing these exclusionary rules. The trial court held that Visa and MasterCard had violated section 1 of the Shearman Antitrust Act by enforcing their respective versions of the exclusionary rule. As a result of the court’s decision, an issuer of one of these network’s cards has the option to issue cards of any other network (a Visa issuer could now issue MasterCard, American Express, and Discover cards). Network officials from Visa told the authors of the GAO report that they actively compete to retain the issuers on their network and interchange fees play an active role. Government intervention in this market led to an unintended side effect of increased interchange fees, and raising the cost of accepting the cards even further rather than lowering it. According to the GAO report analysis of Visa and MasterCard’s interchange fee schedules, several of the networks highest interchange fees were introduced after this decision.

Furthermore, payment card networks maintain a number of rules related to the terms on which merchants accept cards. The rules, which vary between the networks, generally require the merchants to accept all of the payment card networks’ cards in all of their locations on all of their transactions (no minimum and maximum purchase amounts) and to route the clearance of all transactions made using the network’s cards through their network. The rules also forbid merchants to discriminate among the networks’ cards (including surcharging or differentiating between their basic cards and reward cards), or against the payment card network in favor of other card networks. Merchants argue that payment card network rules forbid them from passing along interchange fees to card users, a large portion of the fees are ultimately passed to all consumers in the form of higher prices. Merchants and consumer advocate groups also content that interchange fees are competitively high because merchants can neither bargain over the fees nor pass them along to the card users.

Thus, many merchants find that the cost of accepting payment cards is one of the fastest growing costs of doing business and one that they can do little to control. While merchants receive many benefits for accepting payment cards as we discussed in the business overview section, there is a threshold to merchants’ price elasticity. Accordingly, US merchants have brought litigation and have pushed hard for a legislative solution to what they perceive as an unfair interchange system that enriches the financial institutions at their expense and their consumers’. The Durbin Amendment is the most substantial reply to their campaign to-date.

(ii) What is Durbin Amendment ?

The Durbin Amendment aims to improve competition among payment card networks by reducing the interchange fees on debit cards and allowing merchants greater ability to steer transactions towards lower-cost payment systems.

The legislation contains two operative sections. One section only addresses debit cards. The other section addresses all payment cards, credit and debit.

(i) The first part of the amendment requires that the interchange fees on debit card transactions be “reasonable and proportional to the cost incurred by the issuer with respect to the transaction.” The amendment instructs the Federal Reserve to promulgate regulations for assessing whether interchange fees are indeed reasonable and proportional to the cost incurred by the issuer with respect to the transaction. In determining what fees would be “reasonable and proportional” the amendment directs the Fed to consider the similarity between debit and check transactions that it requires to clear at par. The amendment also provides in its rule making, the Fed shall only take into account issuers’ incremental costs for debit transactions; thereby excluding fixed costs like distribution and other overhead. The Fed is permitted, however, to adjust for issuers’ net fraud prevention costs. The Fed is also permitted to regulate the network fees to ensure that they are not used to reimburse issuers directly or indirectly. Small issuers with less than $10 billion in consolidated assets are exempt from the “reasonable and proportional to cost” requirement, as are government-administered payment cards, and prepaid reloadable debit cards that are not gift cards or gift certificates. The $10 billion exemption is not inflation indexed.

(ii) The second operative part of the amendment prohibits certain payment card network rules that restricts merchants’ ability to steer consumers towards particular payment systems. The small issuer exemption does not apply to this part of the amendment.

(a) First, the amendment prohibits exclusive arrangements for processing debit card transactions. The provision requires that every electronic card transaction be capable of being processed on at least two unaffiliated networks, enabling what is known as “multi-homing (meaning every transaction can find its way “home” over multiple network routings). The requirement that at least two unaffiliated debit networks be able to process each transaction opens the door among networks for transaction processing.

(b) Second, the amendment prohibits the networks from restricting merchants’ ability to decide on the routing of debit transactions. Combined with the multi-homing requirement, this permits merchants to route payments to the networks to the debit network offering them the lowest cost, rather than the current system. This means that card networks will have to compete with one another for merchant routing, presumably resulting in lower interchange fees.

(c) Third, the amendment prohibits payment card networks from preventing merchants from offering discounts or in-kind incentives for using cash, check, debit, or credit so long as the incentives do not differentiate by issuer or networks. The provision specifically does not authorize surcharging, which most card networks prohibit.

(d) Finally, the amendment prohibits payment card network rules that forbids merchants from imposing minimum and maximum transaction amounts for credit cards. Henceforth, merchants will not be violating network rules by refusing to accept credit card transactions below $10, and federal agencies and higher learning institutions may impose maximum amounts. The amendment does not affect payment card network rules’ forbidding minimum transaction amounts for debit cards. There is no exemption from the second part of the amendment for small issuers.

The Fed is required to prescribe the regulations implementing “reasonable and proportional to cost” provision of the Durbin Amendment by April 2011. The Fed is also required to prescribe regulations regarding the multi-homing requirement by July 2011. These provisions of the Durbin Amendment are not self-executing without the Fed’s rule-making. The discounting and authorization of minimum and maximum amounts of credit transactions were effective as of the signing date of the Dodd-Frank Act, on Jul 21, 2010.

(iii) The Fed’s proposal:

On Dec 16 2010, the Fed put the proposed rule-making out for comment and notice before it's Board can vote on the proposed rule. Comments are due by Feb 22, 2011.

During the period from Dec 13 to Dec 23, MasterCard’s stock dropped by 17% from a high of $260 to $216.

"Reasonable and Proportional to Cost" Requirement: The Fed, in its proposal, is requesting comments: one based on issuer’s costs, with a safe harbor (initially set at 7 cents per transaction) and a cap (initially set at 12 cents per transaction); and other a stand-alone cap (initially set at 12 cents per transaction). The Fed did not propose any adjustment to the interchange fee for fraud prevention costs. In order to prevent circumvention or evasion of the limits on the interchange fee that issuers receive from the acquirers, the Fed’s proposed rule prohibits an issuer from receiving net compensation from the networks. If the Fed adopts either of the proposed standards in the final rule, the maximum allowed interchange fee received by the covered issuers for debit card transactions would be more than 70% lower than the 2009 average, once the new rules take effect on Jul 21 2011.

"Multi-Homing" Requirement: The Fed, in its proposal, is requesting comments on two alternate approaches: one alternate would require at least two unaffiliated networks per debit card. For example, a MasterCard signature debit card cannot have a MasterCard branded PIN on the back of the card, but it can have Visa 's Internlink or Discover's PULSE branded PIN). The other alternate would require at least two unaffiliated networks per debit card for each type of cardholder authorization method. For example, each card has two unaffiliated brands for signature debit transaction and two unaffiliated brands for PIN debit transaction. Under both alternatives, the issuers and the networks would be prohibited from inhibiting a merchant’s ability to direct the routing of debit card transactions over any network that the issuer enabled on the debit card.

(iv) Possible Impact of Durbin Amendment

I hope to impress upon you that the impact of the Amendment on MasterCard will be manageable, and that the analysis in the valuation section continues to be valid.

As part of the Fed’s proposal, the Fed required financial institutions to submit data that would help them comply with the Amendments “reasonable and proportional to cost” provision. Examining this data shows that the fees that the networks make on a per transaction basis is fractions of the total of interchange fee and merchant discount fee. For signature debit, the average interchange fee is 56 cents and net (accounting for per-transaction fees, non-transaction fees, and rebates and incentives) network fee per transaction is 5.9 cents for issuers and 4.5 cents for acquirers. For PIN debit networks, the average interchange fee is 23 cents and net network fee per transaction is 1.9 cents for issuers and 3.2 cents for acquirers. However, these numbers are even lower for the large issues because of the rebates and incentives they receive from the networks. Even though, it seems that the Fed’s proposed rule to cap the interchange fee will put pressure on network’s fee charged to the issuer, it seems quite unlikely that this will have a large impact on the networks. Network fees as an overall percentage of the issuer’s total gross interchange revenue today is quite small. Given the statistics from the Fed’s survey, network fees only account for 10% on average but smaller than 5% for the large issuers, who control 70% or more of the debit market. Thus, if these issuers are able to replace their lost interchange revenues from other areas and continue to be interested in maintaining the debit product, network fees will be relatively inelastic to the reduction in interchange fee.

The question then is whether banks will continue to issue debit cards and maintaining a debit card portfolio. Listening to payment card experts, I have learnt that the debit card is not yet another product in the bank’s portfolio. The debit card is an interface to the checking account. In fact, checking account is a misnomer. It should really be called a debit account. The banks aka the issuers have an incentive beyond the interchange fee to maintain the debit card product. It is an important relationship management tool required to attract cheap funding through deposits. In light of the reduced interchange fee, the banks will figure a way out to replace the lost revenue through other sources.

“If you can’t charge for the soda, you’re going to charge more for the burger” –Jamie Dimon, CEO, JP Morgan Chase.

“We’ll go back to where we were 20 years ago where there will be kind of a certain number $5, $8, $9 stated charge for having a checking account every month.” –Kelley King, CEO, BB&T.

“Our goal in the thing is to at least make the thing revenue neutral” –William Cooper, CEO, TCF Financial.

Also, banks will look to alternate products to replace lost revenue like prepaid cards whose interchange fee is unregulated. The economics of higher interchange fees could cause its circulation to go up. Up until now, the banks weren’t too interested in the prepaid product. It was left to merchants like Walmart and H&R block. But the Durbin Amendment may change this situation going forward. Banks could steer its small customers to the prepaid product by levying a hefty charge if checking account dips below a threshold amount and showering awards for using a prepaid card. In such a scenario, MasterCard is positioned better than the other networks to take advantage of the possibility.

Next, let’s understand the impact of the two multi-homing alternates. If the first alternate is chosen, then the cost of processing a transaction (interchange fee + merchant discount fee) on a signature debit will not compete with that of the unaffiliated PIN debit. Off the 8 million merchant locations, only 2 million accept PIN debit. Also, E-commerce merchants and merchants like hotels and car rentals usually only accept signature debit cards. So, in these locations, the merchant has no choice but to accept the signature debit. The first alternate will have virtually no impact on these transactions. At the other 2 million locations that accept signature as well as PIN, the cost of processing a transaction will compete to a certain extent with the PIN transactions but only if the differential between the two is large enough. However, with the interchange fee being capped and acquirer market being competitive, the differential between the total cost of processing a signature transaction and a PIN transaction will be compressed. Even if the networks chose to pass the network fee revenue that they lost on the issuer-side to the acquirers (who in turn will pass them on to the merchants), the total processing cost of signature and PIN would be very close. Merchant's would lose the motivation to provide incentives to steer customers from signature to PIN. PIN simply will start to lose its attractiveness among the remaining 2 million merchants that use it. In the next cycle of upgrades, we think that many merchants will skip upgrading their PIN pads. As this occurs, the mix between signature and PIN should tilt further towards signature benefitting MasterCard (and Visa and Discover). Hence, I believe that the networks will be well protected in the big picture.

The second alternate to multi-homing seems very unlikely. Even the Fed officials (as expressed in the proposed rule-making) think that this alternate is impractical. Implementing this alternate requires significant investment and time required to educate all the parties of the payment card system. Further, it could arguably cause fraud occurrences to go up and weaken its appeal as a product harming the consumers, which is not the intent of the rule-making.

The first alternate, the one that is likely, impacts PIN routing on the signature debit cards. As an example, vast majority of Visa’s debit issuers have exclusive PIN routing contracts with Visa’s PIN brand – Interlink. The first alternate to the multi-homing provision requiring each card to have two unaffiliated networks on the card, opens up the exclusive PIN network contracts on the signature card for competition. Luckily for MasterCard, this is one of those instances where not being a market leader is a good thing. Visa is the market leader in PIN debit, whereas MasterCard is not even in the top four. Thus, MasterCard has a more to gain than to lose due to this aspect of the provision. It could help MasterCard gain market share in this area, but it is a low yielding business so it probably does not matter in the big picture.

Lastly, the provision that merchants can discount any payment card transaction may have negative impact on MasterCard’s US credit card business. It seems like a possibility, but the fact that merchants cannot surcharge dims the likelihood. Mathematically speaking they are the same, but discounting causes a consumer behavior that is a lot less pronounced than surcharging. Besides, merchants have thinner margins and may not be able or want to provide cash discounts. The possible incentives could be a dedicated debit line or coupons. The minimum and maximum limits may reduce the number of transactions but its hard to quantify the impact it may have on MasterCard’s US credit business.

The important conclusion from the above discussion is that the concerns about Durbin Amendment as it applies to MasterCard seem overblown. The losers in this case seem to be the community banks and the consumers. You may ask why community banks if they are exempt from interchange fee cap, but I will leave that discussion to some later time.

Risks: MasterCard is facing litigation in many countries globally. Management thinks that pending litigation that can have meaningful impact have already been reserved on the balance sheet (and we excluded them in our calculation of excess cash & securities). However, if any of the litigations had an unexpectedly large negative outcome, MasterCard’s equity could get wiped out. Also, regulation like one in the US in the debit card business or in its international activities could negatively impact its business and earnings power.

Disclosure: Long MA. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any security. Please do your own research before taking any action regarding any security mentioned in this article. The author takes no responsibility for any errors in this article.

Resources:

Rishi Gosalia is a private value investor based in Austin, TX. Rishi currently works in a management position in the software industry. Rishi graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 2003 as a Distinguished Scholar with an undergraduate dual degree in Computer Science and Pure Mathematics.

http://www.ePINDebit.com http://www.iPINDebit.com http://www.e-PINDebit.com http://www.PINDebit.mobi